ARCHAEOLOGY OF IMAGES N.13

The Buddhist

“Legend of the White Crow” or of the “Five Buddhas”.

By Vittorio Roveda

This paper

describes a popular narrative of the birth of the Five Buddhas as shown in

Cambodian, Laos and Thai iconography. The legend, as childish it may seem, explains

the origin of the Five Buddhas and their association with five different

animals. They became very popular in Theravada iconography of Mainland

Southeast Asia with the spreading of painting from the 18thto the19thcenturies.

To illustrate the legend of the White Crow we use an

early 20th century painting on canvas (pra bot) and

modern murals from Laos.

In Thai imagery the legend of the White Crow and the

five Buddhas has shifted from a folk tale to a non-canonical Pali Jātaka and

finally reached the status of national Buddhist belief in a site that has became

a centre of pilgrimages.

In the enormous corpus of

Buddhist narratives circulating in mainland Southeast Asia, especially

Thailand, scholarship has rediscovered the Paññāsa Jataka being

a group of non-canonical Jātaka. The Paññāsa stories as well as tamnan

(a sort of chronicles) and legends, were transmitted in writing or orally by

educated people (monks or learned men) interested both in history and legends

for their social-historical meaning. The boundary between legendary and

historical (reality and fiction) is ambiguous and altered in time by changing

ideologies. One of these tamnan is “The

Legend of the White Crow”, a vernacular story about the birth and life-events

of Five Buddha-to-be (Bodhisattva) referred also as Pańcabuddhabyākarana.

In this paper, no specific

reference is made to the any Pali manuscript or ancient Thai text, but only to

the reading of paintings on murals or on cloth, in Thailand, Cambodia (see

Roveda & Yem 2009) and Laos.

1.

Summary

of the legend translated by Swearer.

The

White Crow legend is known in Thailand as Tamnan

Ka Phu’ak; it was translated in

English by Donald Swearer in 2004 (197-205). The story (tamnan) was narrated by the Lord to two rice merchants when resting

under a mango tree.

In a former time, at the beginning

of the first kappa, a white crow

mother nested in a tree on the bank of the River Ganges. She carefully attended

her five eggs (the future five bodhisattvas); after days of brooding she had to

search food and left the nest. A severe storm

developed uprooting the tree that fell into the raging river dispersing the

eggs. When the mother crow flew back and did not find the eggs, she was very

distraught, died broken hearted and ascended to the Mahabrahma Heaven.

The eggs were swept into the Ganges

River. The egg with Kokasandha was found by the queen of chickens who took it

with her own eggs. Shortly after the shell cracked revealing a male child. At

the same time, Konagamana’s egg was found by a serpent (naga), Kassapa’s egg by a mother turtle, and Gotama’s egg by the

queen of the cows. The fifth egg (of Si Ariya Matteya) was discovered by a

lioness.

The respective foster-mothers

nurtured with love their children, born at the same time, the same day tough in

different place. After 12 years, the Bodhisattvas reunited and decided to

become hermits. They left their parent promising to remember the family name

and lineage when attaining enlightenment. Each of the five went into the forest

to practice asceticism and meditation. One day, it happened that the five found

themselves under the same beautiful nigrodha

tree and discovered they had the same father and mother (the White Crow), being

thus brothers. They expressed their determination to follow asceticism till

reaching the enlightenment. At that

moment their white crow mother descended from heaven, with beautiful full

wings.

The Five Bodhisattas rejoiced to be

reunited and agreed to honour their mother and compassion by making a replica

of her footprints. She agreed and gave them strands of cotton twisted in the

shape of a crow’s foot to make a votive lamp[1]

to use for puja until they reached

enlightenment. Later, they made the vow to come regularly the nigrodha tree and construct a special

place to enshrine the relics. They returned to the forest “performing puja with the offering of lamps whose

wicks were made in the shape of a crow’s foot”. The first to attain

enlightenment was Kakusandha, followed by Konagamana, Kassapa and Gotama. The

fifth Buddha will be reborn as Si Ariya Matteyya, for whom the four had agreed

to build a very large reliquary (cetiya)

so that humans can pay respect to relics by worshipping, physically or in their

mind.

Visual narratives of the legend

In my experience, the most complete illustration of

the White Crow is painted on a tall Preah

both I was a able to examine in 2011. It is 1.50 high and 65 cm wide, painted

on thin canvas in thin tempera colours. It has two wooden sticks at top and

bottom, on which a bit of canvas is rolled to allow hanging and stay unrolled.

The legend of the Five Buddha is also illustrated on a

Thai cabinet dated 1850-1900 in the Asian Museum of San Francisco (Pattaratorn

in McGill 2009: 137), where the Five are sitting in hieratic padmāsana position on a pedestal with

their respective animals at the base. Maitreya (or Matteya in Pali) is at the

centre, with a green shrub at the back in the shape of a Bo’s leaf.

Large images of the Five Buddhas are painted on the wall

behind the main Buddha’s icon at Wat Pathumwanaram (Bangkok), a temple

completed by the mid-19th century (during the reign of King Rama IV;

1851-1868). The murals were damaged by

fire and repainted in 1970s, followed by major restorations. Therefore, what we

see now is of the second half of the 20th century. The Five Buddhas

are shown in depicted elaborate niches as Bodhisattvas, in royal costumes on

the lower register and as Buddhas in the upper register. The captions are

written in Pali using Khmer Khom

script.

The narrative mode of the Preah bot, presented here have a

polyscenic-network mode, according with the classification Vidya Dehejia (see

Roveda& Yem 2010:20).

In

the Cambodian (or Thai) prah bot of

Fig.1, the painter used the ‘uplifted perspective’ allowing the display of a

continuous narrative from bottom to top of the canvas following a zig-zaging

path, introducing elements unknown in the legend (as translated by Swearer)

such as a hut with and elderly figure resting in an amok, and a trip on a boat

of the five Bodhisatta. All is painted with attention to details, reminding

miniature technique.

The mural painting of Laos,

narrates the story in single panels monoscenic mode.

They

are on the large wall of the vihara (sin),

painted at large scale in a rough way, using indusdtrial brushes and colours,

in 1991.

There

are no other known illustration of the legends of the White Crow in mainland

Southeast Asia. Therefore our examples cannot be compared in style and mode.

Perhaps they exist in the storages of international museums, on canvas or

manuscripts.

The legend in Cambodia

In Cambodian Buddhist iconography depictions of the legend of

the White Crows, her five eggs and adoptive mothers are unknown in painting,

while common are the adult Five Buddhas named Kappa Buddhas, believed symbolic of the auspicious kappa or era (in Pali or kalpa

in Sanskrit)[2]. They

are often depicted on the ceiling of the vihara, on murals and on preah bots. These five figures are shown

seated on plinths, with their symbolic animal at the base. The five include the

three ‘past’ Buddhas, the ‘historic or current’ Buddha and the ‘future’ (Pali

names in parentheses).

1. Kuk Sandho (Kakusandha), in

monastic attire, over a rooster;

2. Nag Gamano (Konāgamana), in

monastic attire, over a naga, although sometimes a snake

or dragon;

3. Kassapo (Kassapa),

in monastic attire, over a turtle; known also as Mahākāśyapa

4. Samana Gotam (Gotama, the

‘historic or current’ Buddha, in monastic attire, over a cow or bull

5. Sri Ariya Matteya, (Pali: Sri Ariya Metteyya; Maitreya is the

Sanskrit form) always dressed as a prince with a

pointed crown over a simha (ratchasi), which

is a tiger in Cambodia and a lion in Thailand. Maitreya is conventionally

placed in a higher position than the others four Buddhas, or at the centre of

what looks to be a mandala, not to be confused with the māndala of the five jinas of Mahayana. Here, by māndala means a sacred design having mystical

significance.

For the symbolic meaning of Maitreya being at the centre of the

five Buddhas, as in Fig.16 , we refer to the comprehensive study of A. Thompson

(2004:7 and following pages).

When Maitreya is depicted as one

of the Kappa Buddhas on a register of

Preah bots, he occupies

always the extreme position to the right.

In many Cambodian viharas

we have observed painted cement statues of the Kappa Buddhas with Matteya

at the centre, arranged on the altar below the large statue of the Gautama

Buddha.

It has been noted that in Cambodia no strict rules are

respected in the arrangement and the representation of the postures of these Kappa

Buddhas, as their mudra, or hand

gesture, change from one painter to the next (Roveda & Yem 201: 51).

The

importance of Maitreya in Cambodian Buddhism is paramount. Already in

the 16th century (1578), as

attested by an inscription (IMA 2) of Angkor Wat uppermost sanctuary, the Queen

Mother, mother of King Brah Satta, after having donated and consecrated images

of the Buddha, made the vow to be reborn in the time of Maitreya who will lead her to nirvana (Thompson 2004:24).

According

to a local legend, upon reaching Buddhahood, Maitreya will open the stupa, or the mountain, where Mahākāśyapa (this is the Sanskrit

form; Pali is Mahākassapa),

the Buddha Gotama’s disciple, is waiting his arrival, meditating upon the robe

he took from the Gotama (the Buddha) and he will offer it to Maitreya, the new teacher. This legend explains the iconographic association

of the stupa with Maitreya and

specifically with his crown in the shape of a Khmer stupa, or chedey.

With the arrival of Maitreya, Buddhism will flourish once

more, before the ultimate dissolution. Therefore, it is important for

Cambodians to make their offering with the wish to be reborn at the time of Maitreya, at the side of which they

will follow the path to nirvana. In this way, it is believed that one

can reach nirvana, and therefore break the cycle of one’s rebirths. This is why

devotees – long before the 16th century – have hoped to be born in

the time of Maitreya.

In some visual layouts, Maitreya seems to have been inserted

among the other four Buddhas as if he were part of a māndala. [3]

The Five Buddhas are painted on a sequence of panels

below the roof of the monastery’s refectory of Kien Svay Krau (southeast of

Phnom Penh). They are amongst the oldest painting remaining in place in

Cambodia, painted towards the end of the 19th century on cotton canvas applied on wood.

The Five Buddhas are illustrated in parinirvāna [4]

reclining attitude, but with fully open eyes. Even more exceptional is

Maitreya painted in such a circumstance (at least in Southeast Asia), because when Maitreya passed

away in his previous earthly existence he did not enter parinirvāna but the Tusita Heaven (realm of the delighted gods)

waiting for the decline and eclipse of Buddhism to reappear and become the next

Buddha. In Tusita he was met by Indra and Phra Malai.

The legend of is Mahākassapa entering Nirvana is well

known in Northern Thailand and Laos Buddhist literature, but is not included in

the Pali Tipitaka (Lagirarde,

2006:79). Manuscripts exist in the National Library of Bangkok (the oldest

dated 1788, probably a copy of a manuscripts saved from Ayutthaya). It is not

known when the story reached Cambodia, probably by the end of the 19th

century; a manuscript’s copy exist at Wat Unalum of Phnom Penh.

In Sanskrit Buddhism (not in the Pali Canon), the Aśokavādāna narrates the nirvana of the

Five Buddhas (masters of the Law) with emphasis on the use and meaning of the pamsukȗlika, the simple cloth of the monks

(Martini 1973: 59).

At the moment of parinirvāna, the Buddha was wearing the pamsukȗlika of Kassapa, one of the previous Buddha, and gave his

own to his great disciple, inviting him to wear it until his nirvana; the cloth

remained intact until the arrival of Maitreya to whom

Kassapa had to pass the cloth (Mahāvastu

III, 54).

In South-eastern Asian

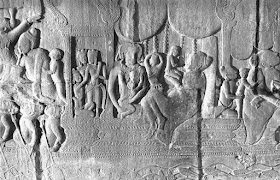

iconography Mahākāśyapa, Gotama’s disciple, is traditionally painted when

attending the cremation of the Gotama, venerating the coffin from which the

feet of the Lord are sticking out. With his arrival the coffin started to

auto-ignite. This event is well illustrated in Khmer and Thai iconography.

The

legend in Thailand

Peter Skilling reports the story of the Five Bodhisattvas

and their specific animals in the Pañcabuddhabyākaraṇa . [5] This non-canonical text includes elements

of the story of the White Crow. Skilling emphasis was on the event of Gotama,

one of the Five Buddha, reaching enlightenment in a Thai sacred site, the stone

slab/dais/platform at Mount Kantharabanphot

in the vicinity of Phra Thaen Sila (Thung Yang). On Mount Kantharabanphot the

Five Bodhisattvas had come together to practice the observance of the precepts.

First Kakusandha and then the

Gotama obtained enlightenment when sitting on the rock slab. The

site has been identified by Olivier de Bernon (2012: 182) (but devotees had

identified it long before) as “Phra Thaen Sila At” in Uttaradit province of

Thailand (north of Sisatchanalai).

The

Buddha predicted that when religion had declined for 2000 years, four kings

will appear and become patrons of Buddhism, and wild animals would become

humans to support Buddhism in this propitious site (Mount Kantharabanphot

area).

The

legend continues asserting that kings will come to help erecting a Buddha image

on the place where the Buddha once stayed and one more king will bring relics

and build stupas.

The

combination of stone slab, presumed relics, stupa and historical records became

pivotal to make the site an important objective of pilgrimages for Thai

Buddhists. Since the time of Sukhothai the site was visited by high members of

the Sangha and of royalty (Skilling: 2009:6).

In time the site suffered a lot

of changes, to the point that when King Rama VI in 1907 (still a crown prince)

went to visit the site and pay respect, he was somehow disappointed not to see

the original stone slab, that had been “covered by wood like a door of Wat

Chinnarat in Phitsanulok” (an important monastery at the time of

Rama VI; Skilling 2011: 15).

The legend in Laos

The east wall of the sin[6] of Wat Phone Say (Luang

Prabang) has large murals painted in 1992. They depict the legend of the Five

Buddhas in 14 panels numbered by the painter.

The first shows two dark (not

white) crows near a nest with 5 eggs, in the foliage of three’s branch hanging

over a river. The second panels show the eggs hatching five small boys, each

under the eyes of five different animals:

a turtle, a naga, a cow, a

cockerel and a ratchasi (mythic

lion). The panels numbered 3-7 display the detail of each boy in the broken egg

protected by one of the animals. The next panel (number 8) shows a large tree

under which sit five hermits, while on the next panel (number 9) and then the

five are paying respects to a large white bird with open wings (their mother)

on a tree branch over them, as related in the text of Swearer. On the lower

registers of the last three panels (10,

11 and 12), each Buddha sits in padmāsana

above a sphere or a circle in which his

specific animal is painted, with the exception of Gotama who sits on a lotus hovering over a cow

(panel 13) and Matteya over a singha

(panel 14). This seems to be the only example of the Five Buddhas depicted on Laos’s

murals.

4.The legend in Burma

In Burmese Buddhism,

iconographic programme the introducing Maitreya with four Buddhas was avoided

(Bautze 2003: 90).The worshipping of the Five Buddhas is intrinsic to

pentagonal temples.

Common at Pagan are the 28 Buddhas of the past painted

on walls of several shrines (Bautze 2003: 80), shown in alternating mudra and differentiated by the tree

under which they mediate besides the name inscribed below the painting as

identified by Horner in her Introduction to the Chronicle of Buddhas (2013:

xli).

Maitreya (‘Mitrya’

in Burma) images are very are in Pagan iconography, where he appears a Bodhisattva

(Bautze 2003: fig.92-94), in princely

attitude wearing jewels, as in the classic and famous painting of Ajanta (late

5th century).

Personal view

The little-known legend of the White Crow was

introduced in the iconography of mainland Southeast Asia in the 19th

century; the legend may have been autochthonous of the northern territory

uniting northern Siam and Laos (Chieng Mai, Lamphun, and Luang Prabang).

In time, the non-canonical “Legend of the White Crow” became

separated from the stories of the Buddha and his four disciples, as narrated in

canonical Jatakas

Artists were given

freedom of imagination to create series of murals instructive and didactic,

becoming thus new visual storytellers, exiting conventional iconographic canons.

The importance of written texts was fading because the

visual narratives on the pagoda murals were more readable than the original

texts and manuscripts, locked in monasteries, not easily available to lay

people

Pali language had gradually lost its meaning dominance as

the language of Buddhism and was transmitted mechanically by chanting monks and

novices. In Thailand the White Crow legend is also transmitted in mixed

Pali-Thai dialects (nisay style in:

Skilling 2009: 180).

In this paper, no reference is made to manuscripts.

One can speculate that many texts have gone into

oblivion because easily and better narrated in iconography.[7] People of Southeast Asia learned more from

the Jataka painted on vihara’s murals

than by listening to monks’ narratives in Pali.

This theory is supported by the flourishing, spreading and richness of

mural painting of Jataka’s themes

from the middle of the 19th century.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chuai, Chuangchunsong, Phra. The

White Crow, The Legend of the Five Bodhisattva, in Thai Phraya Ka Phueak,

Nithan Phra Phothisat Thang 5 Phra Ong, Bangkok: Duangkaeo Press, 2004. (In Thai).

De Bernon,

Olivier,

The status of Pali in Cambodia: from Canonical to Esoteric Language,

in

Buddhist Legacies in mainland Southeast

Asia, ÉFEO Etudes thématiques, Paris, 2006: 53-64

De Bernon,

Olivier,

‘Journey to Jetavana’: Poetic and

Ideological Elaborations on the Remembrance of Jetavana in Southeast Asia,

Buddhist Narratives in Asia and Beyond, Institute of Thai Studies,

Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 2012:177-193

Horner, Isaline

Blew,

The Minor Anthologies of the Pali Canon,

III, The Pali text Society, Bristol 2013 (first published 1975)

Pattaratorn

Chirapravati,

Central Thailand, in Mc.Gill (ed.) Emerald

Cities, Asian Museum of San Francisco, 2009: 136-37

Bautze-Picron Claudine, The Murals of Temple 1077 in Pagan (Burma)

and their Innovative Features, 2010: Orchid Press , Chieng Mai, 2003

Bautze-Picron Claudine, The Buddhist Murals of Pagan,

Weatherhill, Trunbull, USA, 2003

Roveda, Vittorio & Sothon, Yem, Preah Both,

Buddhist painted scrolls in Cambodia, River Books, 2010

Skilling, Peter, Buddhism and Buddhist Literature of South-East Asia.

Selected Papers, Fragile

Palm leaves Foundation, Bangkok and Lumbini, 2009

Skilling, Peter & Santi,

Pakdeekham, Pilgrimage to the “Stone

Seat (Phra Thaen Sila-at)”, International Conference on Buddhist

Pilgrimages in History and Present Times, Lumbini, International Research

Institute, Lumbini, Nepal, 11-13 January 2010

Thompson,

Ashley, The Future of Cambodia’s Past, a Messianic Middle-Period

Royal Cult, in History, Buddhism and New

Religious Movements in Cambodia, edit. Marston J. and Guthrie E.,

University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 2004

Utube - Google,พระยากาเผือก, contemporary

information and children video on the White Crows.

Captions:

Fig.1

– Prah Bot showing the full legend of

the White crow. The canvas is probably of Thai origin around the beginning of

the 20th century (220cm x 75cm; private collection).

Fig.2

- Detail of Fig.1showing (in clockwise sequence) five eggs retrieved by, a tiger (ratchasi), a cow, a cockerel, a naga and a turtle on the shore of a

lake, sea or river with fish and prawns.

Fig.3

- Detail of Fig.1 displaying the two white crows and their empty nest. On land

are the Five Buddhas as young boys in front of their custodian animals.

Fig.4

– Detail of Fig.1 (top portion) showing the Five Buddhas and their adoptive

parents.

Fig.5

– Detail of Fig.1 (top portion) showing the Five Buddhas going by boat towards

the caves to practice meditation under the guidance of a master-hermit (on the

painting shown suspended in mid-air).

Fig.

6 - Detail of Fig.1 = Then figure meditating in isolation is probably Matteya

Fig.7

- Painting on cloth applied to wood, showing Matteya (tiger) reclining in paranirvana position. Old refectory of

Kien Svay Krau (south-east of Phnom Penh, Cambodia). Probably end of the 19th

century.

Fig.8

- Companion of No.7 ; Gotama (bull or cow)

Fig.9

- Companion of No.7 ; Konacagama (dragon)

Fig.10

– Companion of No.7;Kaklusanda (cockrel)

Fig.11

– Companion of No.7; Kassapa (turtle)

Fig.12- Prah Bot with the Buddha’s sarcophagus, and Kassapa venerating his feet before the cremation. (124 cm x 82cm; probably Thai, end of the 19th century; private collection).

Fig.13 - Wat Phone

Say (Luang Prabang, Laos), mural painting showing six elements of the legend of

the White Crow (see text), painted in 1992.

Fig.14 – horizontal

sequence of Hieratic Five Buddhas and their symbolic animals, common on the highest

register of many pra bots(Cambodian) and on some

murals in Cambodia and Thailand).

Fig.15 – The Five

hieratic Buddhas with their respective symbolic animals. Detail of a Camboian pra bot (private collection); mid-20th

century (private collection)

Fig.16 - The Five

Buddhas with Matteya, as prince at the center. Wall painting in the monastery

in the first enclosure to the South of Angkor Wat.

Fig.17 – The Five

Budha in hieratic alignment. Wat Patumvaran (Bangkok). The upper registered refer to the five Buddhas. The lower register refer to them when they were princes.

[1] a small clay lamp with a crow’s foot-shaped

wick was widely used in northern Thailand during religious festivals (Swearer

2004: 197)

[2] Kappa or Kalpa is a unaccountably long period of time, an aeon

[3] For the symbolic

meaning of Maitreya being at

the centre of the five Buddhas, as in Fig. 5, we refer to the comprehensive

study of A. Thompson (2004:7 and following pages).

[4] The

Pali Mahāparinibhana suttanta of the Diga Nikāya is the oldest original text

about this event.

[5] Taken from the translation (Pali-Thai) inserted in Vol.2 of

the Paññāsa-jātaka (Skilling

2009: 2).

[6] In

Laos, sin corresponds to the Thai vihan and the Cambodian vihara; congregation hall.

[7] Texts reappear, in

fragments of variable size, as quotations, written in Sanskrit or Pali, in many

publications as embellishments and un-necessary demonstration of scholarship by

authors.