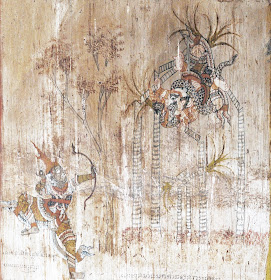

Wat Bo: My Concluding Personal View on the Murals

In my book of 2015 (In the Shadow of Rama) I took into consideration the Thai Ramakien as the most explanatory text of the murals of Wat Bo. Now I start to give more wait to the story of a Cambodian text, the Trai Beht, especially in the narrative of Mi Chak (in French by Bizot 1989).

In my book of 2015 (In the Shadow of Rama) I took into consideration the Thai Ramakien as the most explanatory text of the murals of Wat Bo. Now I start to give more wait to the story of a Cambodian text, the Trai Beht, especially in the narrative of Mi Chak (in French by Bizot 1989).

The Trai Beht and the version

of MiChak explains most of the events painted on the western wall of Wat Bo,

but in a different sequential order of painted murals,

In the 1960s, the bard Mi Chak narrated what he

had memorized from a palm leaf manuscript of the monastery of Angkor Wat South

in 1920 (Bizot 1973) when he was a bonze for nine years. Because his excellent

memory, diction, and clear voice he soon became a celebrated storyteller. He

was engaged by François Bizot to record his story on tape in 1969 to be published it in1989 (Roveda &Yem,

2009: 238) This is the text to which I

prefer to use, being neatly narrated and illustrated with the murals of the

Silver Pagoda of Phnom Penh.

Over the years I have formulated the theory that

in Cambodia the Khmer elite used, since the 8th century, the Sanskrit

language that had its best development in the 12th century with appreciation

of Sanskrit Valmiki’s Ramayana. It seems

that Sanskrit gradually disappeared by the 15thcentury with social,

economic and religious dramatic changes. Sankrit had been the language of the

aristocracy and purohitas (master

gurus), the Cambodian language used by lay people becoming populist already

from the time of Jayavarman VII. Pali language was exclusive of the samga.

All Southeastern Asia countries were touched by

the Indian Ramayana, each localizing

it to their own needs and costumes, sometimes Buddhisized (seeds in the Reamker)

or left in its original vernacular form (the TraiBeth of common

people).In some countries, the story of Rama became almost

unrecognizable (Paula Rich man 1991).

In Southeast Asia it developed by itself amongst

the lay population by storytellers, shadow theatre and ballet, in Cambodian

Middle Age the only form of education and entertainment

There is also the possibility that the Traibehet may have been taken as a booty

by the Siamese during repeated invasions of Cambodia. Or it may have been

developed by Khmer artists that worked in Siam, as prisoners or as free students

of Siamese culture. It may be that the Siamese had independently developed

their own rendition of Rama’s epic rendered in writing by the scribes composing

the Ramakien by order of King Rama I (1782-1809).

It may be, finally, that the sponsor of Wat Bo

was a Thai monk or erudite person.

1 – with the Traibeht starting with the creation of the Cosmos with Anukaro and

Anukara and continue till the adventures of Ravana

2 – with the Ramaker of MiChak starting with the creation of the world.

2 – With the Ramakien starting with Vishnu, in his white boar incarnation,

killing the demon Hiran who wanted to steal and destroy Earth.

3 –Not from the Cambodian ReamkerI that does not have any kind of

introduction, The narrative starts well later, with the story of Ram killing

the crow Kakanasur and of the episode of Janaka adopting Sita during the royal

plowing ceremony (Jacob 1986: 1,2).

I

believe that the monks and painters knew about the Cambodian Trai Beht hidden in the palm laves

monasteries or Institutions but preferred to use a popular printed version of

the Siamese Ramakien easily available

from Bangkok. The Trai beht is known

amongst the clergy, being painted on the external wall of Wat Bo Kraom (Siem

Reap) and of Wat Sampov (Battamnbong).

My

assertion that Wat Bo’s murals depict events of the Thai Ramakien rather than the Cambodian Reamker may contradict the expectation of nationalist readers.

Furthermore the Ramakien may disturb

those interpreting the story of Rama as the story of a Bodhisatta by giving

priority to Buddhist meaning to the Reamker,

believing that the populistic Ramakien has marginalized ‘cleaner’ versions of

the story of Rama. I share the opinion of Paula Richman (1991:4), in believing

that the appropriation of the story by a multiplicity of groups means a

multiplicity of ideological concerns of each Ramayana text (and its derivatives) reflects the social location

and ideology of those who appropriate it.

The

date of the Trai Beht manuscripts is

attributed to the “Middle Period” (1500-1900) of the history of Cambodia and

the Ramakien to early 1800. To

know if the Trai Beth was earlier than the Reamker

or vice versa will be a serious cause of controversy until further evidence

will be discovered.

In my interpretation of Wat Bo narrative (Ramakien) I willingly stood away from

any religious, social and ideological context normally elaborated by the preferences

of the reader.

I

believe in here we are dealing with a masterpiece, not only for the remarkable

ability of the painters, but for the intellect of the person/s who ideate and assemble

the images respecting, with verve, the thread of the original text.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Giteau,

Madeleine, Les

représentations du Rȃmakerti dans les reliefs modelés de la région de

Battambang (Cambodge); in: Living in life in accord with Dhamma: papers in

honor of professor Jean Boisselier on his eightieth birthday, Silpakorn

University, Bangkok, 1997: 229-244

Giteau,

Madeleine, Note sur

l’iconographie des peintures murales du monastère de Vat Bho (Siem Reap), Udaya, 5, Phnom Penh, 2004 : 19-32

Goldman, Robert P and All., The Ramayana of

Valmiki, Volume I-VI, Motilal

Banarsiodass, Delhi, 2006-2009

Hoc Dy, Lpoek Angkor Vat (Poeme d’Angkor Vat),

Association Culturelle “Pierres d’Angkor”. Choisy-le-Roi (france), 1985, 120

pages

Jacob, Judith, Reamker (Ramakerti),

the Cambodian version of the Ramayana, The Royal Asiatic Society. London

1986

Khing, H. D., Un Épisode

du Ramayana Khmer, L’Harmattan, Paris 1995

Khing, Hoc Dy, Lpoek

Angkor Vat (Poeme d’Angkor Vat). Association Culturelle ‘Pierres

d’Angkor’, Choisy-le-roy, France, 1985

Khing Hoc Dy, Contribution a l’histoire de la Littérature Khmère, Vol I, Époque

Classique, XV-XIX siècle, L’Harmattan, Paris 1990.

King Rama I, Ramakien by King Rama I, Volume 1 [บทละครเรื่องรามเกียรติ์ พระราชนิพนธ์ใน Ramakien byKing

Raama I. Volumes 1-4 [บทละครเรื่องรามเกียรติ์ พระราชนิพนธ์ใน พระบาทสมเด็จพระพุทธยอดฟ้าจุฬาโลกมหาราช, เล่ม ๑-๔] (Bangkok:

Fine Arts Dept, 2540 BE (1997 CE).

Leclère Audemart, Le

Buddhism au Cambodge, Paris 1899

Leisen, Hans and von Plehwe,

Esther, The murals of Wat Bo pagoda in Siem

Reap. State of preservation-First results, Udaya, Phnom Penh, Number 4, 2003

Martini, F., La Gloire de Rama, Reamkerti, Les belle

Lettres, Paris,1978

Népote,

Jacques, & Gamonet Marie-H, Intoroduction aux peintures du Ramayana de Vat Bo,

Peninsule, No.45, 2002 :5-88, Centre National du Livre, Olizane, Paris

Olsson, M.D., The

Ramakien, A prose version of the Thai Ramayana, Praepittaya Company Limited

Partnership, Bangkok, 1968

Pech Tum, Travel, Sbek Thom, Khmer

Shadow Theatre, Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University and UNESCO,

1995, 190 pages,153 figures

Pou, Saveros, Etudes sur le Reamakerti(XVI- XVII siècles),

Publications de l’EFEO, Vol. CXI, Paris, 1977[2]

Pou, Saveros, Les traits Bouddhiques du Rāmakerti, BEFO, LXII, EFEO, Paris, 1975

Pou, Saveros, Reamakerti (XVI-XVII siècles), Publications

de l’ EFEO, Vol.CX, Paris, 1977[1]

Pou, Saveros, Reamakerti II ,), Publications

de l’ EFEO, Vol.CXXXII, Paris, 1982

Richman, Paula, Many Rāmāyanas, University of

California Press, Berkley, 1991

Roveda,

Vittorio, Das Ramayana in der Templekunst, in Angkor, Göttlisdhes Erbe Kambodschas, Kunst- und Ausstellunghalle

der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, 2007,123-131.

Roveda,

Vittorio, Dundubhi in Ramayana

narratives of Cambodia and Thailand, in Ramayana

in Focus, Gauri Parimoo Krishnan editor, Asian Civilization Museum,

Singapore 2010, 123-131.

Roveda, Vittorio, Images of the Gods, River Books, Bangkok, 2005

Roveda, Vittorio, Sacred Angkor, Narrative reliefs of Angkor Wat, Weatherhill &

River Books, June 2002.

Roveda,Vittorio, Valmiki and the Ramayana in a relief on Banteay Chmar, ‘Udaya’, 4,

Phnom Penh, September 2003:53-57

Roveda,Vittorio and Yem, Sothon, Buddhist

Painting in Cambodia,

River Books, Bangkok 2009

San, Phalla, A

Comparison of the Reamker Mural Painting in the Royal Palace of Cambodia and

the Ramakien Mural Painting in the Grand Palace of Thailand, Master

degree Thesis, Chulaonghorn Univerisity,Bangkok,2007

Shastri, H.P., The Ramayana of Valmiki, 3 vols, Shanti Sadan, London, 5th

reprint, 1992.

Shastri, Satya Vrat, The

Rāmakien and the Vālmiki Rāmāyana: a study in

comparison., 2nd

International Ramayana Conference 1968, Thailand,

Thai-Bharat Cultural Lodge, Bangkok 1987:6-15

Siyonn, Sophearich, The life of the Ramayana in Ancient Cambodia, Udaya, 6, Phnom

Penh,2005, 45: 72, Proceedings of the second Ramayana Conference of 1986,

Thailand, Thai--Bharat Cultural Lodge Publication, pages 33-35; 11

illustrations.

Vickery,

Michael, History of Cambodia, Summary

of lectures at the Faculty of Archeology Royal University of Fine Arts, The

Pre-Angkorean Studies Society, Phnom Penh, 2002

Reap

2000.

The

End

Bangkok January 2017