ARCHEOLOGY OF IMAGES NO.5

Cambodia’s Wooden Buddha statues

By Vittorio Roveda @ (Copyright text and pictures)

Admin: Sothon Yem

Amongst the most neglected Khmer cultural elements are the wood statues of Buddha. I try to fill the gap by re-elaborating what Gateau and Boisselier wrote in the past, together with my own personal observations, but a lot of fresh research is needed. It is a very hazardous task because the statues that we have now in museum or private collections, do not have any reference to the sourcing monastery or site of origin, and time of carving and no references in Cambodian literature. Dating is impossible, apart by style reference. In the long periods 14-18th century statues were rare due to the political situation and general impoverishment of the country, and the attack of termites. Most of the statues we see at museums are of the 18-19th centuries.

Foreword Statues must have required particular skill in which the artist could see in intuitively the image of the Buddha to start carving away what was not needed to make it concrete. There must have been workshops, from the home-restricted where the father carves some parts and the son or a friends other parts, to the sponsored workshop of monasteries where a team would attend to the making a complete statue.

The head volume was probably the first delineated, followed by the carving out the material for evidencing the torso and the abdomen, keeping in mind that the body had to be covered by a transparent thin robe (uttarasanga).Some pieces, such as the forearm and the hands were carved separately.

I believe there were worships with a master carver instructing his collaborators how and what to carve. One must have been in charge to carve the head, another the body, and finally one to arrange the base in which the statue’s feet had to be inserted. I believe that exceptionally a single woodcarver did the entire job alone, I prefer to see it done by a small wokshop. In addition there were specialists for lacquering and gilding.

The costume of the Budda

To study Buddha’s statues it is essential to know about Buddhist monk’s costume.

It includes 3 elements (Fig.10):

Antaravasaka adjusted on the hips, covering the lower body, supported by a belt from the 18th century.

The uttarasanga, monastic robe like a gown.

The sanghati, a thin cloth carried on the shoulder.

Standing Buddhas do not carry the sangathi but the uttarasanga covering the shoulders; walking Buddhas have a naked right shoulder. Sitting Buddha’s images have the sanghati placed on the left shoulder. Walking Buddhas, rare in Cambodia but common in Thailand with an ample uttarasanga leaving the right shoulder naked, but covering the left shoulder and arm.

The uttarasanga is thin, almost transparent, revealing the antaravasaka because the Buddha’s body emits light lightening his costume from inside to outside. The Buddha can appear in simple monastic robes or in princely costumes, reflecting his origin. His hairstyle is composed by a layer of hair covering the ushnisha (cranial protuberance) from which exits a pointed tuft of hair like a lotus bud or sometimes taking the shape of a flame, symbol of the light of knowledge (Giteau 1975: 46).

Typical of Cambodian adorned Buddha is the head covered by a combination of a large diadem (or tiara) and the mukuta, a heavy cover-chignon (Fig.18). Another characteristic is the tiara covering all the nape and extending slightly over the temples, a feature known since the 10th century Cambodia (Boisellier1966: 249) with rich ornamentation. The heavy tiara or crown is identical to that of Khmer kings (from the time of Koh Ker), defining a unique category of the ‘Crowned Buddhas’. The feet’s heals were not carved on the tree trunk: being the centre of gravity. The frontal part of the foot, with the toes, was carved on the block of the plinth the pedestal (see Fig. 9).

In the statues I had the chance to view quickly in 2008 at the National Museum of Phnom Penh, the uttarasanga covers the body until the wrist and the two layers of the fabric are falling from both the forearms till reaching the lower leg. The antaravasaka had a long strips like scarves falling from the belt at the belly. This vertical strip became more and more ornate with time, till to be covered with series of small glass rectangles, or other forms of carved decoration (Fig.53)

The attitudes and mudras. The repertoire of mudras (position of arms, legs and body) is quite limited in Cambodian sculpture in contrast to the variety in Thailand, and Burma.

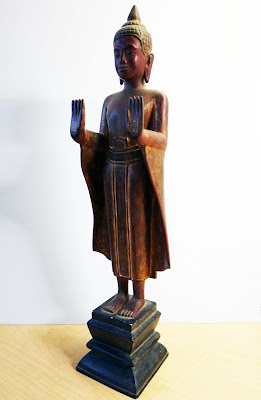

The standing Buddha’s sculptures examined here show in preference both hands in the double abhaya-mudra, or vitarka-mudra, the reassuring gesture (dispelling fear)(Fig.8), or with one hand raised in abhaya-mudra, and the other lowered along the body, indicating quieting down, peace and distension (Fig.7 right).

Rarely the Buddha was carved holding the alimony-bowl or both hands accepting Sugiata’s gift of holy rice. In some images, the right hand is placed against the chest, the palm facing forward, perhaps a variation of the abhaya-mudra? Most of the times the left hand’s palm is carved the ‘wheel of life’ (Chakra) one of the distinctive birth marks of the Buddha. Both hands with the chakra are also present,

Wooden sculptures of the seated Buddha represent him seated with crossed legs (virasana), with the fingers touching the ground or the edge of the seat (Bhumisparsa-mudra), or both resting, one on the other, on his lap. He is at the moment of the Enlightenment

There are also statues in wood Buddha in the Parinirvana or mahaparinirvana mudra, reclining on his right side supporting his head with his right arm, at the moment of his entering the Great Total Extinction (and physical death); in contrast, when his body is reclining on the left side, he may symbolise the form in which the Buddha appeared in the sky at the Miracle of Sravasti.

Technology

Cambodian wood standing Buddha’s statues were generally sculpted in the hard-wood of tatrau or of the krakoh, which was not resistant to humidity and termites like the Koki wood used for the columns of the viharas. Sculptures were roughly shaped out directly from a tree-trunk using conventional tools. Expertise was required for carving the main part of the body and - in some case - shoulders, upper-arms, forearms, hands and earlobes (Fig.8-9) were carved separately. These were later applied to the main body using wooden or metal pegs, and the joints, cracks and gaps were filled with brown-red glue. The back side was left flat un-adorned and re-joined making sure that the uttarasanga was in continuous flow. This technique was very appreciated for the standing Buddha. (Giteau 1975: 29)

The hairstyle consisted in a thick layer of hairs added to cover the ushnisha, from which a conical element exits. This is not a flame as in Thai Buddhas, but simply a conical shaped device (Fig.21). After the wood images were completed, a layer of black lacquer (not exceeding 4mm) was applied. A much thinner layer of red lacquered was added, essentially to give a warmer tone to the gilding that constituted the top layer of the sculpture. The statue was then polished to obtain a brilliance similar to that of the Buddha’s robes donated to him by one of his followers. When Ananda laid down the gifted robe over the dying Buddha, the Master emitted a bright olden light surprising all (Giteau 1975: 35).

Then came a new technique that had started in Burma from where it spread to Siam and Laos, soon reaching Cambodia. At those times interaction amongst countries and artists was common. The technique consisted in making a thick lacquer, and apply it on the previously lacquered smooth surfaces and design ornaments to the costume. It may also been arranged in lines or droplets to further enrich the decoration. This type of decoration evolved, especially on the necklace and the tiara or diadem. On the pectoral decoration in large circles of leafs remind the Ayutthaya’s art. The antaravasaka look Siamese in many specimens of wooden Buddhas (Giteau 1975: 193).

To further embellish wood statue, artists introduced new materials glued to the wood, such mother-of- pearl, semi-precious gems, and, more often, vitrified lead, and thin circular small mirrors (sequins). The Buddha’s eyes were generally looking down in contemplation, covered by the upper eyelid. When the eyes were visible, they were animate by using white polished bone or white stone with the pupil painted black (Fig.20). The carved umbilicus of a statue was sometimes ornate with a small piece of mirror or of rock-crystal.

These decorative incrustations were known in the 13th and 14th centuries, but became very popular in the 18-20th centuries.

Myanmar artists went further by using the dry lacquer technique. The approximate outline of the sculpture was made from clay over which were laid strips of cloth impregnated with lacquer sap. This was then covered with further layers of lacquer sap and lacquer putty (sap mixed with sawdust) and modelling the final outlook. Once the layers of lacquer were set, the clay core was removed. The more common wood Buddhas were very elegant lacquered and gilded and decorated with sequins, especially from the end of the 17th century until the 19th century. Images of the 19th century enrich museums and collectors. There is no carved wood in the statue and therefore these Buddhas are referred as ‘Lacquer Buddha’.

Representations of the Buddha

In Cambodian wood sculpture there are various types:

1) The standing adorned (crowned) Buddha, in hieratic position with a massive necklace and the crown of Khmer type, large shoulders, prominent pectorals, face with square jaw, eyebrows united like in the statues of Angkor Wat style. The uttarasanga has a simple decoration; the belt is large. His face has severe expression; his extended earlobes carry heavy earnings. It conveys little spirituality; he is the chakravartin of Buddhism (Fig.17left, 18). Statues with pointed nose, large, arched eyebrows clearly designed, earlobes composed in 2-3 layers are attributed to the Siem Reap School.

2) The standing unadorned Buddha in monastic robe, smaller, typified by the hairstyle in small pointed curls also over the ushnisha. The hairs of the Buddha did not grown after the tonsure and on statues are represented as groups of small cones usually arranged geometrically in lines (Fig.20bis). No crown. It has unadorned extended earlobes. The ushnisha is something conical, often with hairs carved in lines, and a tuft of hair similar to the flame of Sukhothai’s Buddhas. When bulbous it may remind the La Na style (Fig.17right, Fig.20)

3) The sitting Buddha at the moment of Enlightenment, with the right hand touching the ground (Fig. 5, 6) or Bhumisparsa mudra.

4) The dying Buddha, in parinirvana mudra (rare)

5) A few statues of kneeling worshippers or acolytes have also survived (Fig.27). They were carved probably carved from a single piece of a large tree-trunk because no junctures exists under the thin lacquered coating. These statues of worshippers are not older than the mid-17th century. In a beautiful statue of as young worshipper (a boy?) gentle and devoted, of the National Museum (Phnom Penh), at the level of the stomach, over the belt, a small rectangular cracking is visible, covering an ancient reliquary (Fig.25,26). A Cambodian mixture was used as a heavy lacquer was oleoresin (a resin solution in fatty oil) like a gum, to cover the cracks caused by the site of the reliquary.

Finally I must describe another rare technique by which after the wood statue was finished, it was covered with a layer of dark lacquer and let to set, then the artist started to carve the lacquer down to the wood, designing thick decorative elements, interweaving leaves branches and flowers over the entire dress of the Buddha, as if the Buddhas was wearing a decorate robe (Antaravasaka and uttarasanga).

The face was gilded and completed with eyes I doubt made of white material (stone, bone or Ceramics?) with pupils painted black. The facial expression is typical Khmer, as in the un-decorated Buddha of Giteau (Fig.21), that was probably produced in the 19th century.

This technique is the same of “sgraffito” consisting in scratching through one layer of plaster or lacquer covering the sculpture, so as to reveal another contrasting underlying colour. This technique was used in Sawanhalok brown-and-white ceramic of the 15th century Thailand (information kindly offered by Dr. Dawn Rooney, on 30-7-2016, who I thank here).

Historiography

The first wooden Buddha images were produced in Preangkorean time in the region called Funan, located to the western side of the Mekong delta (in modern Vietnam). Two recent publications have documented a few much eroded wooden Buddha, one by Khoo in 2003 and another by Tingley in 2010 (Fig. 12-14).

Koo reports that several wooden sculptures have survived, surprisingly well preserved in the damp clayish-soil in locations of the Mekong Delta, including Thap Muoi, Phong Me, Binh Hoa, Ma Noli and Thap. Carbon 14 dating gives an average age around early 6th century. Some wooden statue, much eroded were looking like in the Amaravati style were found at Go Thasp, dated 5th Century CE (Miksik 2003: 25) (Fig. 13).

From scattered localities of the Mekong Delta are a few eroded statues of standing Buddha and Bodhisattva are illustrated by Ha Du Cannh and J.C.M. Khoo and described at page 136 Fig.VI-1 to 4.

The catalog of the Museum of Ho Ci Min, written by Nancy Tingley (201:126) describes and illustrates one beautiful standing Buddha statue (Fig.1 and 11bis), one amongst other statues ranging in measure from 30 cm to almost 3 meters, usually in double abhaya-mudra, with smiling face and eyelids downcast. In the statue chosen by Tingley it seems that the Buddha holds the monastic robe with his left hand the mudra being undetectable (N. Tingley 2010: 126). Similar wood Buddha appeared in the Bangkok’s antiques market in the early 2000s, but some revealed to be modern copies perfectly executed and artificially aged; good fakes! The statue of the Ho Ci Min museum may be the same one that was illustrated in 1966 by Boisselier (1966, plate XLI, fig.1), with the provenance of the ‘Plaine des Joncs’.

Other wooden Buddha were excavated by the team of Miriam Stark (USA) and Koo, together with several collaborators, in the region of the Mekong delta and in the modern village of Oc Ceo that at the beginning of the 2nd century CE. was a commercial center of the western Southeast Asia maritime trade, in the so-called state of Funan (Fu Nan).

Also Chinese records indicate that in early 5th century CE. Buddhism was popular

in Funan and that the region was visited by Chinese monks. Buddhism was an important

element in the relationship of Funan with China (possibly Mahayana rather than Theravada).

In general, it is evident that the many excavated figures of Buddha and Vishnu (carved in stone) in the same area could fit into the ‘Pre-Angkorean style’. The wood Buddha’s statues compose a group that at the moment cannot be classified apart from attributing all of them to the period between the 3rd -10th century CE (average 6-7th century CE),the Pre-Angkorean.

Boisselier was of the opinion that (1966: 266), all the Pre-Angkorean Buddhas (stone and wood), demonstrate the influence from southern India, with variable localization and adaptation of lost prototypes. This point of view conflicts with that of Robert Brown (1994: 11) who is of the opinion that the sudden appearance in South-east Asia of the Buddhas with double vitarka-mudra (without clear Indian prototypes) cannot be explained unless recurring to Grinswold’s theory of the error of the copyist (copying a broken Indian statue) assuming that both hands were in the same mudra. “One model, one artist, one modified copy engendering a complete series”.

Dupont (1959) noticed that several Buddha’s statues were packed in the Preah Pan of Angkor Wat (Fig.31). This was a wing of the cruciform complex of Angkor Wat that Buddhists closed to make a sacred reservoir, filling it with lots of statues and paraphernalia that was scattered in and around the temple. The wood statues were made using the same technique of attaching the forearm and hands by a peg as seen above, their decoration consisted mainly of branches of vegetation made of lacquer. The statues were produced from coexisting workshops in which two or three generations of artists had evolved new techniques and different canons.

Giteau reported that in 1975 the Angkor Conservation of Siem Reap stored some 1000 statues with a remarkable percentage of good quality made by a variety of workshops. Wood statues stored at the National Museum of Phnom, are perhaps fewer, but of a quality similar to those of Siem Reap (Giteau 1975: 5).

In the long periods 14-18th century, statues were rare due to the political situation and general impoverishment of the country. Most of the statues we see at museums are of the 18-19th centuries, the few that survived pillaging, termite’s attack and collectors’ mania.

Unfortunately, in general the lack of precise provenience of the statues, the absence of dated specimens, the lack of research and published material, make impossible for me to present a meaningful classification. I do not know the exhibits of wood Buddha at the new Angkor National Museum of Siem Reap. Rich countries of Southeastern Asia preferred bronze for religious images (Thailand). Laotian wood sculptures of the standing Buddha have the peculiar attitude of having at least one of the long arms extend at the side of the body. In Myanmar (Burma) was achieved the maximum decoration of Buddha’s wood statues. This is exemplified by the Mandalay Buddha, where the young serene Buddha is wearing a large uttarasanga with the decorated edges floating in the wind (Fig.64). The use of myriads of sequins cannot escape the viewer. This style repeats on the crown and sometimes over the chignon.

In the 18th century most of the images of Buddha in wood were made in the province of Battambong when the province was under Siamese domination, introducing Thai elements influencing Cambodian art. The Cambodian king and his entourage of pandita (religious savants), family, servants, musicians, and dancers were taken in captivity or for ransom to Bangkok by the Siamese king. Khmer architects, musicians, sculptors and specially painters learned their art in Bangkok. Also the clergy was attracted to Bangkok where the full Tripitaka, basic Buddhist Pali text, was available.

Extended periods of political and social unrest caused the dispersing of several local workshops. In Thailand, the uninterrupted demand for religious items initiated by the Thai kings for monasteries erected under their sponsorship, gave rise to mass production or repetition of the same Buddha image with only variations in the shape of the crown (usnisha and diadem) and of the face. Each face has a different expression, mainly juvenile and serene. They were made in bronze and then heavily gilded. Possibly, the arrival of beautiful bronze statues, easily replicable, caused the loos of interest in wooden Buddha.

The wood-statues of the 19th century are very similar to the older ones (17-18th); those carved in the Battambong area are so close to the Thai that can be considered as part of Thai art (Fig.52). Cambodian wooden Buddha kept their special local characteristics that clearly separate them from similar wood statues from Thailand, the Cambodian being less ornate, simpler. With the advent of the second part of the 20th century, devotional statues were made of cement, stuccoed and painted in brilliant colours (oil paint). Small monochromatic glass statues of Buddha were also available. The best example is the Emerald Buddha of the Royal vihara of Phnom Penh, probably made in France by Baccarat crystal’s factory.

Giteau reported that in 1975 the Angkor Conservation of Siem Reap stored some 1000 statues with a remarkable percentage of good quality made by a variety of workshops. Wood statues stored at the National Museum of Phnom, are perhaps fewer, but of a quality similar to those of Siem Reap (Giteau 1975: 5).

I am very surprised by the fact that wood statue of the dying Buddha in the parinirvana-mudra, are never mentioned in books of the greatest scholars and I had to recur collectors and internet pages to have some picture of them. It seems that this idiosyncrasy for reclining wood Buddha extends to museums.

Conclusion

In my research on Post-Angkorean wood Buddha’s statues I conclude saying that I could not see more of what previous scholars did, meaning the division in two groups: adorned and unadorned forms and in a general dating 14-20th century.

An evolution can be see ion the type and amount of added decoration and the type of material used for it. But this should be farmed in the chronology context.

The majority of the statues illustrated in here, most carved from the 17 to the 19th century

Those with added carved lacquer were probably made in the 18th-20th century.

In general, statues of worshippers were made in monastic costume representing disciples of the Buddha, kneeling close to their master. They have the look of the devatas (angelic beings) that had been carved on the pediments of Ta Prohm, Tonle Bati and Preah Pithu X, a few centuries before.

I also agree with the evident conclusion that in mainland Southeast Asia, wood Buddha statues were rare over centuries because, anytime there was the opportunity, bronze was preferred material for donation to the temple, rewording higher merits than wood. Wood was a cheap perishable material. Nevertheless artist managed to carve masterpieces out of it. I am surprised of the lack of interest in these artifacts. Only in the 20th century two scholars were interested (Giteau and Boisellier).

The statue of a worshipper that is now at the Phnom Penh Museum is one of the most remarkably example of the post-Angkorean art, embodying the Buddhist spirit of humility and renunciation, carved in the very hard krakoh wood, and attributed to the 17thcentury. It is certainly my preferred wood sculpture and with it (Fig.25, 26) I like to terminate my modest contribution.

Bangkok, August 2016

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boisselier Jean, Asie du Sud-Est, Vol.1, Le Cambodge, Picard, Paris, 1966

Boisselier Jean, The Heritage of Thai sculpture, Waterhill, New York & Tokyo, 1975

Brown Robert.L., ‘Rules’ for changes in the transfer of Indian art to Southeast Asia, in Ancient Indonesian Sculpture, KITLV Press, Leiden, 1994

Garnier Pierre and Nafilyan Guy, Cres Christian, Nafilyan Jaqueline, Khmer Art in rserve, Editions Européennes Marseille - Provence, 1997

Giteau Madeleine, Iconographie du Cambodge Post-Angkorien, Publ. EFEO Vol.C, EFEO,Paris,1975

Giteau Madeleine, Art et Archéologie du Laos, Editions Picard, Paris (75006), 2001

Groslier George., Note sur la statuaire khmer ancienne, Etudes Asiatiques, EFEO XIX-XX, 2 vols.1925

Koo James C.M (Ed.), Arts and Archaeololgy of Fu Nan, Orchid press, Bangkok, 2002

Karow Otto, Burmese Buddhist Sculpture, White lotus, Bangkok 1997

Koo J.C.M., Art and Archaeology of Fu Nan, Orchid press, Bangkok, 2003

Malleret L., L’Archéologie du Delta du Mekong, 3 vols, Publication de l’EFEO, Vol.XLIII, 1959-1963

Tingley Nancy, Arts of Ancient Vietnam, Asia Society and The Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston 2010

Bangkok, August 1016

======================================================== = = = = == =

ILLUSTRATIONS of Post-Angkorean Wood Buddha.

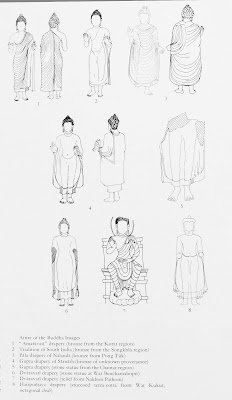

Fig.1-2 - Drawings

taken from Boisselier 1975 to shows the dressing of Buddhist monks

Fig.3-7 - Drawing taken from Boisselier 1975 to shows the various attitudes

Fig.8-9 – Drawing

taken from Giteau 1966 showing the emplacement of additional pieces carved

separately and the insertion of the main sculpture into its pedestal (Fig.9)

Fig.10-The main

costume of the Buddha or of a simple standing monk and its nomenclature

Fig.11 and 11b –

Wood’s massive statue of Buddha in monastic aspect, excavated from the Mekong

Delta area, presumably Funan period, Vietnam National Museum. Photograph taken

from the Catalogue. Probably 6th century

Fig. 12,13 - Early pre-Angkorean eroded Buddha statues recently excavate in eastern

Mekong Delta.

Funan period, probably 6th century

Fig.14 - Early pre-Angkorean eroded Buddha statues recently excavate in eastern Mekong

Delta.

Funan period

Fig.15 - Two wooden Buddha statues from the National Museum of Phnom Penh. To the left is the smaller figure monastic

aspect (unadorned Buddha) and to the right the Buddha’s crowned hieratic aspect

(adorned Buddha). Both examples are in the double abhaya-mudra. Post-Angkorean (from Giteau 1975)

Fig.16 -– Standing

unadorned gilded Buddha in abhaya-mudra from

Leah (Pursat). Statue corresponding to that of Fig.15 left(from Giteau 1975).

Fig.17 – Two tall

Buddha from the National Museum of Phnom Penh. The statue to the left is the

typical adorned (crowned) standing Buddha, the statue to the right is of a

Buddha simply in monastic attitude. (V.Roveda photo)

Fig.18 – Standing

adorned Buddha in double abaya mudra. Probably

the same of Fig.17left (from Giteau 1975)

Fig.19, 20 -

Eroded wooden statue of a monastic Buddha in double abhaya-mudra.

Probably 14th

century, National Museum of Phnom Penh(from Giteau 1975)

Fig. 20b – Buddhas

hair arranged in lines at 45 degree to create small cones usually arranged

geometrically in lines (Photo Jaro Poncar)

Fig.21 – Hieratic

face of an adorned Buddha with painted eyes (From Giteau 1975)

From Giteau

1975,Fig.56,

Fig. 22– Partially

gilded wooden statue of the Buddha in single in a mudra altered by the bunch of

dry flowers. Only his left arm is in Abhaya-mudra.From

Giteau 1975, Fig.20, found in Leach (Battambong). Probably 18th

century

Fig.23 - Detail of

a crowned Buddha in the double abahya

mudra, From Giteau 1975, GVFig.19. found at Wat Srai Sar Chhor (Srei

Santor), Pre-Angkorean

Fig.24 – Detail of

an unadorned Buddha statue in double abahya-mudra.

National Museum of Phnom Penh (Photo V.Roveda 2008)

Fig.25, 26 - The

well-known wood statue of the kneeling worshipper (a samanera?). A little over

the navel a rectangular shape is visible; it covers the space for enclosing

relics. Another worshipper is shown to the right. Fig.26 shows the detail of

the headgear worn by the worshipper.

National Museum of

Phnom Penh (Photo V.Roveda 2008).

Fig.27 - Three examples

of kneeling worshippers at the National Museum of Phnom Penh.

The central one is

the most complete and suave, illustrated here in Fig.24 and in most books of

Khmer art (Photo V.Roveda 2008)

Fig.28 – Detail of

the crown of a standing ornate Buddha, Phnom Penh National Museum. (from Giteau

1975)

Fig.29, 30 –

Assemblage of standing wood Buddha in the Angkor Conservation, August 2002

(from Giteau 1975)

Fig.31 – The

sacred room open in the 20th century to reveal a storage of Buddha

statues and paraphernalia.

Fig.32-35 –lacquered seated Buddha in the Bhumisparsa mudra. This statue displays the peculiarity to have the external lacquer skin sculpted, incised to reveal the underlying gilded layer similar to the ‘sgraffito’of the ceramic technique, probably 19-20th century. (Private collection, photo G.de Bernis 2015)

Fig.36 - A wood

Buddha statue ornated with mirror tesserae in the crown and necklace. Small

glass pieced ornate to tip of the earrings. Probably 18th century.

National Museum of Phnom Penh

(photo??????)

Fig.37,38 - Wood

sculpture of an ornate Buddha (typical Buddha

paré of the French), in single abhadya-mudra,

Musée Guimet, Paris. Dated post-Angkorian (XVIII – XIX cent,)

(Photo Sothon Yem

2013).

Fig.39 - Heavily

ornate statue from Giteau 1975,Fig.56. Post-Angkorean

Fig.40,41 - Small

size wood standing Buddha in double abhaya-mudra.

This specimen comes from a sculptor working for the “Artisan d’Angkor” in 1980. The production of this and elegant

lacquered statuettes continues till, today. Siem Reap, end 20th century.

(Photo L. Roveda

2015)

NOTE. Phtographs 42-55 are taken from the publication

Kheer art in reserve by P. Garnier and G.Nafilyan published in 1997. The

photographs were taken by Jaqueline Nafilyan. To them goes my gratitude for

allowing me to reproduce these masterpieces in my pure research study.

Fig.42 – A

delightful Buddha’s statue head dated as 13th century by P.Garnier

&G. Nafilyan1997, page 66, National Museum of Phnom Penh.

Fig 43 – Fragment

of an adorned Buddha, from P.Garnier &G. Nafilyan1997, page 74, National

Museum of Phnom Penh.

Fig.44 - Standing

unadorned Buddha’s statue probably in

double abhaya-mudra, from P.Garnier

&G. Nafilyan1997, page 76, National Museum of Phnom Penh.

Fig.45 – Standing

crowned adorned Buddha’s imposing statue, identical to our Fig.18,

from P.Garnier

&G. Nafilyan1997, page 68, Post-Angkorean

Fig.46 – Standing

unadorned Buddha’s statue probably in double abhaya-mudra , from P.Garnier &G. Nafilyan1997, page 78,

Post-Angkorean

Fig.47,48 – An unadorned Buddha in the double abhaya-mudra, the right (Fig.48) is an udorned Buddha with the mark of the chakra on the palm of the left hand, from P.Garnier &G.

Nafilyan 1997, page 62-63, National Museum of Phnom Penh.

Fig.49- Crowned

and Adorned Buddha’s statue, probably in double abhaya-mudra, from P.Garnier &G. Nafilyan1997, page 67,

National Museum of Phnom Penh.

Fig.50 – A

kneeling worshipper, from P.Garnier &G. Nafilyan1997, page 62-63, National

Museum of Phnom Penh. Post-Angkorean

Fig.51 – Adorned

Standing Buddha statue, with decoration of glass/mirror in the crown,

necklace, belt and

drapery descending from the belt, from P.Garnier &G. Nagilyan1997, page 73,

National Museum of Phnom Penh. The Thai inspiration is evident.

For comparison, wooden Buddhas from southeast Asia are illustrated below

Fig.52 - Standing Thai Buddha with traces of laquer. Lopburi school,13-,14th century

Private collection, (Bangkok) From Boisselier 1975,Fig.167

Fig.53- Head from

a Buddha image, Wat Rajadhani Sukhothai

U thong style,

14-15th century National Museum Sukhothai

From Boisselier,

1966, page 3

Fig.54 – Standing Thai Buddha’s statue in double abhaya-mudra.

The statue is in perfect conditions with the shiny black lacquer and some gold

decoration, from P.Garnier &G. Nagilyan1997, page 69 .Presently in Thailand

Wat standing at.

Fig.55 -Standing

adorned Buddha image, lacquer and mother of pearl. Wat Wixun (Luang Prabang,

Laos). The extension of the long arms at the sides of the body is typical

Laotian. The statue is ornate with the lacquer which is is engraved to produce

designs and space flor glass decorations. The tiara is pointed end rests on a

flattened base and of a shape that appears at the end of the 18th

century. From Giteau 1975, Fig.129, page 161

Fig.56 - Two of

the largest ornate lacquered Buddha statues in the cave if Pak Hu, 19th

century, from Giteau,1975, Fig.132, page 162. This cave is on a cliff on the

Mekong and is a favourite tourist destination from Luang Prabang. 20th

century. From Giteau 1975, Fig.132, page163.

Fig 58 – Ornate

Buddha seated in bhumisparsa –mudra in

part eroded by termites. (Coll.Vat Vixun) Luang Prabang, 19th

century, from Giteau, 1975, Fig.131, page 162

Fig.59 – Sketch by

Madeleine Giteau exemplifying the late adorned Buddha from the 19-20th century

Laos. Notice the 4-polinbted crown, the large pectoral decoration and other

elements ornate with flowery design and trellises. From Giteau 1975, page 159.

Fig.60,61 – Burmese Buddha

in royal attire, gilded wood in the verada-mudra

(granting wishes).

Probably from the

Pagan period but retouched in the 17th century with coloured glass

inlay, from Karow, 1991, fig.41.

Fig.62-63 - Brawn

lacquered gilded statue of crowned Buddha seated in bhumisparsa-mudra, Mandalay 19th century, from

Karow,fig.70.

Fig.64-65 –

Standing Burmese Buddha ,Wood with lacquer and gilt.

The robe folds

abundantly at the sides with borders encrusted with coloured glass pieces. The ushnisha is entirely covered by rounded

cut- small coloured glass, no finial. In his right Hand he holds a small myrabolan fruit. Mandalay style, 19th

century, from Karow, 1991, Fig.71

Fig.66,67 – Gilded Shan Buddha in royal attire standing with floating lower part of the uttarasanga that has heavy decorated

bands with glass inlays and sequins. Mandalay style. In Burma, statue of this

style are called the Jumbapati

Buddha. Konbaung period (end 17 mid 19th centuries), from Karow

1991, fig.46

Fig.68,69 – Seated

Buddha in bhumisparsa-mudra. Lacquered

gilded wood. The back of the throne has an opening for relics or ashes of the

deceased. 19th century, from Karow 1991, Fig.69.

Fig.70,71 –

Standing Buddha holding the sides of his robe. His right hand holds a small myrabolan fruit. Black lacquer, gilded

with sequins inlay at the edge of the robe and on the crown band but not on the

usnisha. Mandalay style, 19-20th

century (Photo V. Roveda 2016).

By Vittorio Roveda @ (Copyright text and pictures)

Admin: Sothon Yem