The Jatakas of

Wat Bo (Siem Reap)

By

Vittorio Roveda and Sothon Yem

(@Text and pictures copyright)

When visiting the monastery of Wat Bo in Siem Reap to admire the

marvelous Ramayanic murals, one cannot miss noting the painting of Jatakas, one behind the central east

door, and the very degraded other on the lower part of the west wall.

We will explain why we attribute the eastern mural to an event of the Vessantara Jataka (Cowell No.540).and the western one to the Nimi Jataka (Cowell No.541). The

interpretation of these two murals is our own and has never been previously

published by other authors. The reading is quite difficult because of the poor

state of preservation, but as usual in iconography we look for clues. In the

case of the eastern wall, the revealing clue was the old man with a sash

(Jujuk) and for the western wall, men tortured in hell.

The Vessantara on the east wall.

The narrative of the Vesantara Jataka

is very well known and we have reported it in our book on Buddhist painting in Cambodia (2010) and in the smaller book on Pra Bots ( 2010).

The mural painted behind the eastern door (Fig.00) depicts a single episode of the long Vessantara Jataka.(Fig.1

and Fig.2); the murals have been degraded by dirt and neglect.

Once, in the kingdom of Kalinga, there was a

village named Dunnivittha where an old Brahmin lived called Jujaka (also

written Jujuk). He had given his money on loan to a certain Brahmin family, who

in his absence spent it all. Now when Jujuk asked for repayment, they offered

instead their young daughter Amitta.

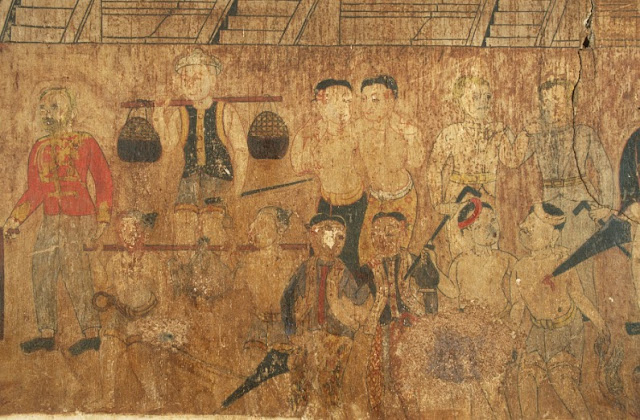

We believe that the mural depicts the scene

when old Jujuk was walking in the village market with a stick and carrying a

sash on his shoulder (Fig.3, bottom

left corner, perhaps in the presence of Amitta’s parents carrying umbrellas. On the red skirt of a lady with umbrella, it

is possible to perceive the face of a girl and her sarong below, probably

Amitta.

The market is composed of rows of stalls

selling merchandise, mainly textiles (see Fig.2) built on a terrace, probably

in view of the raining season floods.The crowd is international, including

Westerners (most in uniform, wearing shoes) and Arabs in addition to local

people. Two men carry a small animal hung by the legs on a wooden pole on their

shoulders (Fig.4). In a shop, a

woman is fanning her face while waiting for customers; in another a woman is

arranging her hair looking into a square mirror, she sells textiles, umbrellas and

food in jars. In another shop (Fig.6)

a chinaman smokes beneath a large pendulum clock of a type we estimate was known

in Cambodia only from the middle 19th century. In another shop, men

attendants are smoking tobacco pipes. All the shops have textiles exposed on a

wire. We know from Zou Daguan that textiles in Cambodia were very appreciated

and used as symbol of the social status of the owner, especially fabrics with

some rich design such as those woven with continuous branches with leaves and

flowers ( “ramage” in French ), could only be worn by the mandarins. The very

best of textiles came from Siam and Champa, but the most expensive were from

India (in Pelliot, 1951: 13).

In some shop are vases for the sale of their content

(medicine, food or drinks) but indicating a variety of goods available at the

market.

Amongst the crowd at the market, a couple of embracing

friends is depicted (Fig.7). At the

end of the 13th century, Zhou Daguan noticed that there were many young

gay boys (French “mignons” in Pelliot’s 1951: 16) who went to the market every

day in groups of ten or more to attract the attention of the Chinese in hoping of

rich presents.

Although none of these details or the specific

event are written in the Cowell Jataka,

the market scene has been frequently painted by Khmer artists, including on

murals at Kampong Tralach Leu and Sisowath Ratanaram (Roveda &Yem, 2009: 60;

see also, Roveda & Yem 2010: 105, Fig.136), and has become part of the

repertoire of daily life, village and market scenes, not to mention those

carved at Bayon.

Nimi Jataka on the West wall

The large mural (between the two western doors) in the lower part of the

western wall is mostly deleted and unfortunately only some patches with images

are still visible. It is difficult to make sense of the images scattered on the

dusty discolored old wall. The clue for interpreting this mural as the Nimi

Jataka (or the Pra Malay story) is the presence of damned suffering seen in the

tortures inflicted to sinners painted on Cambodian murals (see Roveda &

Yem, 2009: 06).

A summary of the story is necessary to

understand the images. In the 541 Jataka

of Cowell (1995, VI: 53) is written that the first of the Videha’s Kings

ascended to the Brahma heaven after ruling for thousands of years. Earlier, he

had decided to abdicate in favor of his son when he discovered his first white

hair and to retire to an ascetic life. At death he ascended to the heaven of

Brahma from where he looked down upon his family and noticed that all but two

of his successors had renounced the world, becoming ascetics. He decided to be

reborn on earth as the son of his descendant, the king of Mithila, and rule the

country until his first gray hair, when he would become an ascetic once again.

For this, he reincarnated as the boy prince of Mithila, with the task to round

off the royal dynasty, like the hoop of a chariot wheel; hence his name, Nimi-kumara

or Prince Hoop.

As a king, Nimi was exemplary, ruling

rightfully, giving alms, caring for the poor. He inspired many of his people to

lead such a good life that at death they were raised to Indra’s heaven.

Nimi had always in mind the question “which is more fruitful, the holy

life or giving alms?” a question heard by Indra, who was obliged to descend to

earth to explain that holy life was more fruitful with meditation reaching the

gods in heaven and sometimes nirvana, although almsgiving was also beneficial.

Indra reported Nimi’s interest in this matter to the gods of the Thirty-three

Heavens, who asked him to bring him to their heaven. Therefore, Indra sent his

celestial chariot driven by Matali to pick up Nimi. The charioteer asked Nimi what he preferred to visit first: the hells or the

heavens. Knowing that certainly he would visit the Heavens, Nimi urged him to

drive to see the hells.

At Wat Bo the mural depicting the sinners’ figures is so degraded that

only their tracing is visible, no color having survived. We have tried to

improve the vision and understanding by using Photohsop.

It is easier to read the story from the right to left. Therefore, we

start from the right side of the mural (Fig.1).

The picture improved by Photoshop shows a figure wearing a crown (Nimi) seated

at the door of the main room, with red walls of a small palace (Fig.2). In the lateral smaller rooms

are probably courtiers. To the left, a little below, is an annex pavilion with

blue walls but interconnected by sets of staircases. In this blue pavilion are

six figures wearing tall pointed crowns, kneeling with their hands in anjali position. Outside, to their left

is a group of 7-8 bareheaded commoners also kneeling in veneration attitude lead

by a crowned man. Over the palace, it is still possible to view angels dancing

in the sky amongst clouds. This scene may represent Nimi giving a sermon to his

royal colleagues and commoners.

To the left of this scene is the chariot with

one parasol of rang pulled by a white steed. It is the divine chariot sent by

Indra (Fig.3). The charioteer Matali

is standing on the ground looking at Nimi seated on the chariot indicating the

direction to follow: go first to the Hells. Just in front of the horse the

painters painted the hells with two strong executioners throwing sinners into a

flaming brace. Higher up flies a black crow carrying something in his beak.

On the wall of Fig.3, there

are traces of rows of people suffering the tortures of hell:, two sinners being

thrown by guardians into a cauldron in flames (Fig.4). Below these images and bottom right side is painted the celebrated

spiky tree (Fig.5) on which sinners are

forced to climb until their flesh is totally lacerated. Nearby, hell’s guardians grab the tongue of

sinners with tongs; others extract the entire tongue or cut the head. Sinners are

shown suspended on a pole being dropped into a hot cauldron. Other sinners are

shown pounding red flesh into a mortar; a sinner is crucified with a spinning

disk on his head; others are thrown into a cauldron full of heads or skulls. A

sort of serial garroting instrument (looking like a stepladder) is shown to the

extreme left of the picture. This is visible at the center of the picture that

follows (Fig.6), close to a large

brown graffiti that marks the transition to another scene. To the left (Fig.7) is a small flimsy building (an

opium bedroom?) hosting a person with crossed legs apparently smoking a long

opium pipe as the one better visible at the market scene of the Vessantara

panel. Unfortunately, only the lines drawn to paint the figure are preserved. At

the entrance of this room (?), a man seems to be writing on a black tablet the

consumption of opium (of his customer?).

Looking further to the left (Fig.7), a small palace is shown with a

figure on the entrance terrace. This figure is wearing a royal crown and is flanked

by a smaller figure also wearing a crown and dark brown background suggesting

the side room of a palace where there are courtiers with hands in anjali. The figures outside the palace are also in

this position of respect.

It is possible to interpret the scattered

images of this large mural as part of the Nimi

Jataka. In the right part of the panel, the main figure in the palace with

several rooms is that of Nimi, giving a sermon to figures kneeling in anjali . Then he visits the hells on the

chariot sent by Indra eventually encountering Yama (?), the ruler of the hells,

and his assistant, judging people for

their sins like that of the man smoking opium in the near pavilion.

Comments on the hells

The concept of hell(s) does not exist in Buddhism, there is no eternal

punishment since everybody will be reborn, unless nirvana is achieved. Sinners

may be reborn in one of the number of hells. It is believed that there are hot

and cold hells, each with numerous subdivisions, where evil-doers are tortured

by demons until their bad karma is exhausted and are reborn in other forms.

What is more relevant is far of hall. The possibility to be condemned to one of

the worst tortures until total repayment .of their sins.

Fear plays an important role in all

religions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cowel,E.B. and all., The Jatakas, The Pali Text Society, Oxford, 1995

Pelliot, Paul, Mémoire sur les Coutumes du Cambodge de Tcheou Ta-Kuan, version ouvelle,

Maisonneuve, Paris, 1951

Roveda,Vittorio

and Yem, Sothon, Buddhist

Painting in Cambodia, River Books, Bangkok 2009

Roveda Vittorio and Yem Sothon, Prea Bots, River Books, Bangkok 2010

CAPTIONS NIMI

|

| Fig.2 – Wide angle view of Nimi’s departure on the divine chariot leaving his royal palace to visit the hells. |

|

| Fig.3 – Detail of Nimi’s chariot with the white steed and Matali as charioteer. To the left hell’s scenes start to be visible two justiners throwing two men in a burning cauldron. |

|

Fig.4 a hell’s scene with various types of tortures (see text). |

|

| Fig.5 – Detail of the hell’ spiky tree that adulterers are forced endlessly to climb to reach their partner who is falling to the ground while the other reaches the top (see text) |

|

| Fig 7 - Detail of fig.6. |

CAPTIONS VESSANTARA

|

Fig.00 – The western wall with one episode of the Vessantara Jataka is painted to the right of the central door

|

|

| Fig.1 – The eastern inner wall with the painting of a Jataka to the right of the central (open) door. |

|

Fig.3 – The Vessantara Jataka mural photographed by Jaro Poncar in 2004. |

|

| Fig.5 – Enlargement of the figure of Jujuk and possibly of his girl Amitta. |

|

| Fig.7 – Detail of two boys clinging together in the market; they probably are gay youths as observed by Zu Daguan. |

To the left of the man with red uniform jacket and shoes (a westerner?),

two men carry an animal suspended by the legs from the pole thy carry on their

shoulders.

No comments:

Post a Comment